MARS - Multi Asset Reconstruction for Simulation

I got tired of making 3D assets by hand.

That’s it. That’s the origin story. I needed a quick custom simulation scene for robot training, and watching a 3D artist spend hours on a single coffee mug made me want to flip a table. So I built a pipeline that takes a photo and turns it into a physics-ready 3D scene automatically.

I called it MARS.

The Problem Was Simple

Robots learn by doing. They need to practice picking up cups, moving blocks, clearing tables. But they can’t practice on real objects because they’ll break everything while learning. So we use simulations.

The bottleneck? Creating those simulated environments. Every object needs a 3D model, a collision mesh, physics properties like mass and friction. A typical tabletop scene with six objects could take days to create manually.

I just wanted to point at a photo and say “make this into a simulation scene.”

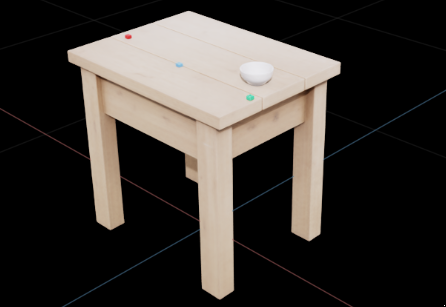

A single photo is all MARS needs to create a physics-ready simulation scene. (Image generated using Nano Banana)

The Solution: Chain the Right Models Together

The key insight was that all the pieces already existed. I just had to wire them together. But “wire them together” undersells it. Each model has specific strengths and weaknesses, and the trick is pairing them so one covers for the other.

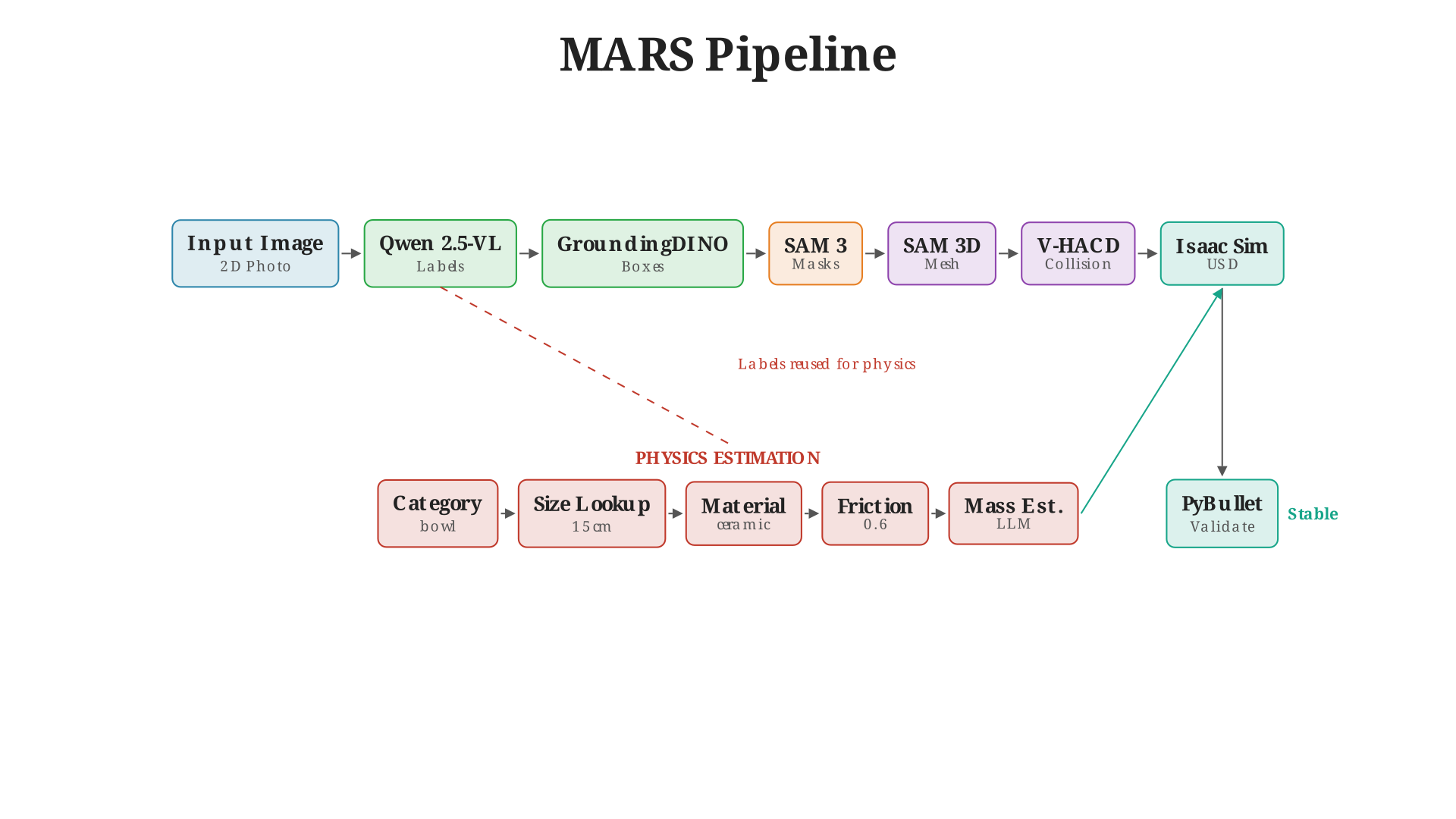

The MARS pipeline. Each stage feeds into the next, with quality checks at critical junctions.

Step 1: Figure Out What’s in the Image

To go from an image to a 3D scene, I first need to identify every object. Enter Qwen 2.5-VL, a vision-language model that can look at a photo and tell me what’s there.

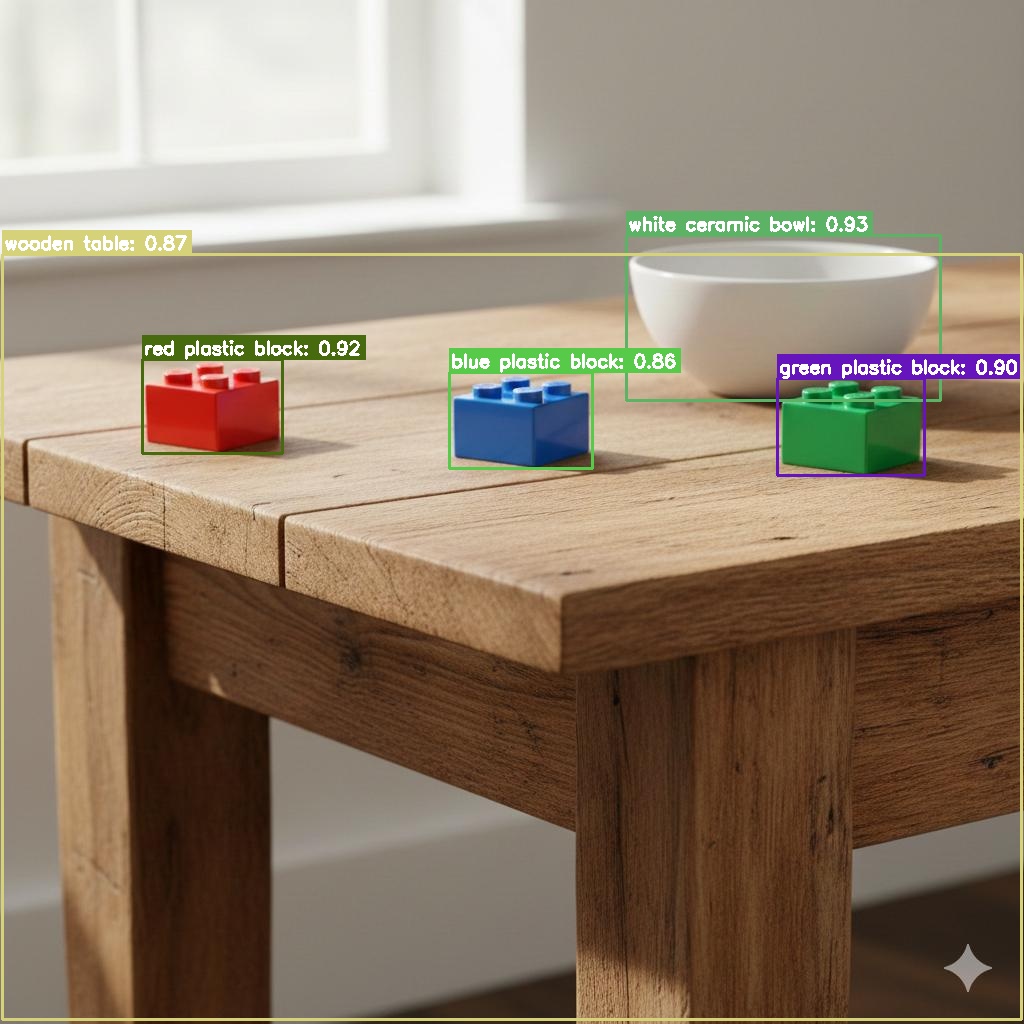

Here’s a concrete example. I point the pipeline at a photo of a tabletop with some blocks and a bowl. Qwen looks at it and returns:

- "red plastic block"

- "green plastic block"

- "blue plastic block"

- "white ceramic bowl"

Notice how it doesn’t just say “block” four times. It gives me descriptive labels: colors, materials, specific object types. This matters later when I need to estimate physics properties and scale objects to real-world sizes. A “red plastic block” gets different friction than a “white ceramic bowl.”

But here’s the thing. Qwen is great at naming objects. It understands context. It knows that shiny white thing with curved sides is a bowl, not a plate. But ask it to draw a bounding box around that bowl? The box will be… approximate. Sometimes it clips the rim. Sometimes it includes the shadow. Qwen wasn’t trained to be a precision detector.

So I paired it with GroundingDINO. DINO is a different beast. Give it text prompts—”white ceramic bowl”—and it will draw a precise bounding box around exactly that object. It’s grounded in language, meaning it uses text to guide its attention. The catch? It needs those text prompts. It can’t tell you what’s in an image; it can only find things you describe.

See where this is going? Qwen tells me what objects exist. GroundingDINO tells me where they are. Neither alone is enough. Together, they’re unstoppable.

I also run NMS (non-max suppression) at the end because sometimes both models get excited about the same object and give me overlapping detections.

Qwen identifies "white ceramic bowl" and "red plastic block." GroundingDINO draws precise boxes around each.

Step 2: Cut Out Each Object

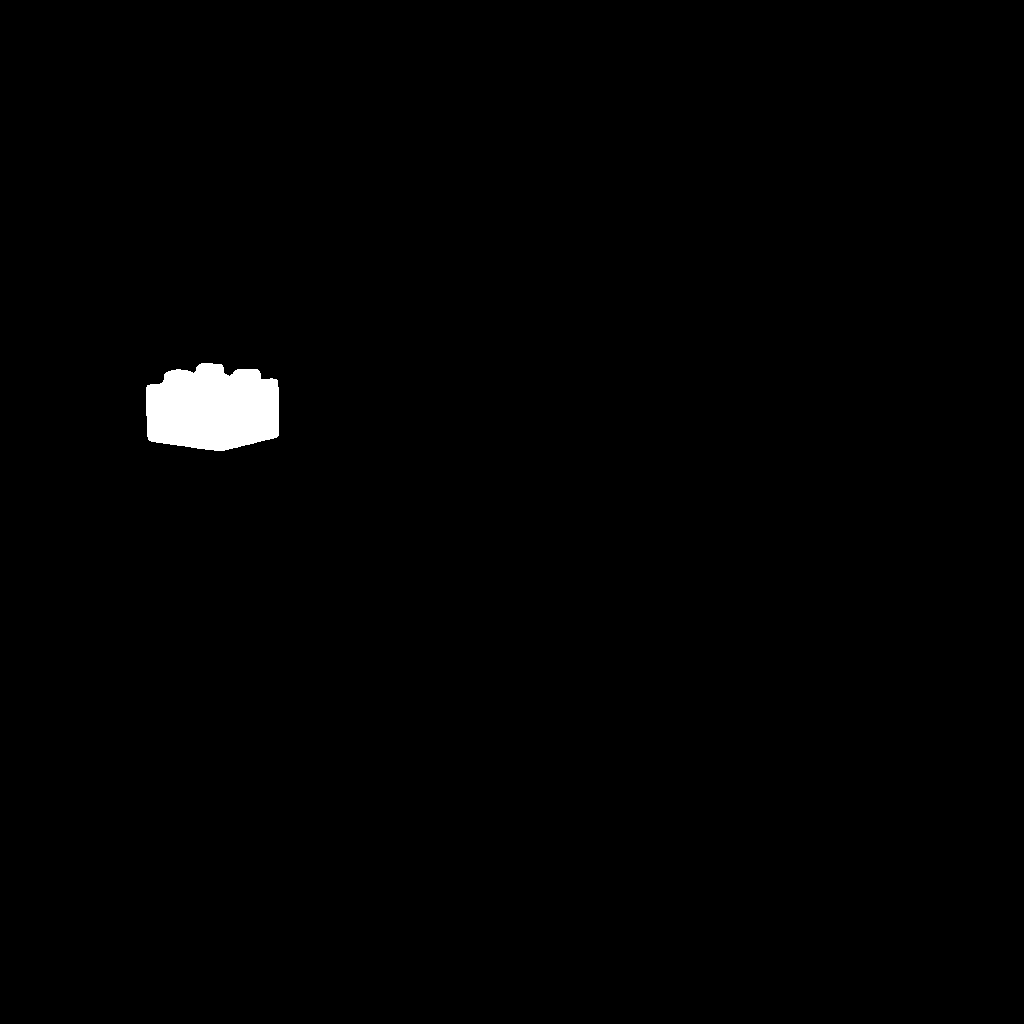

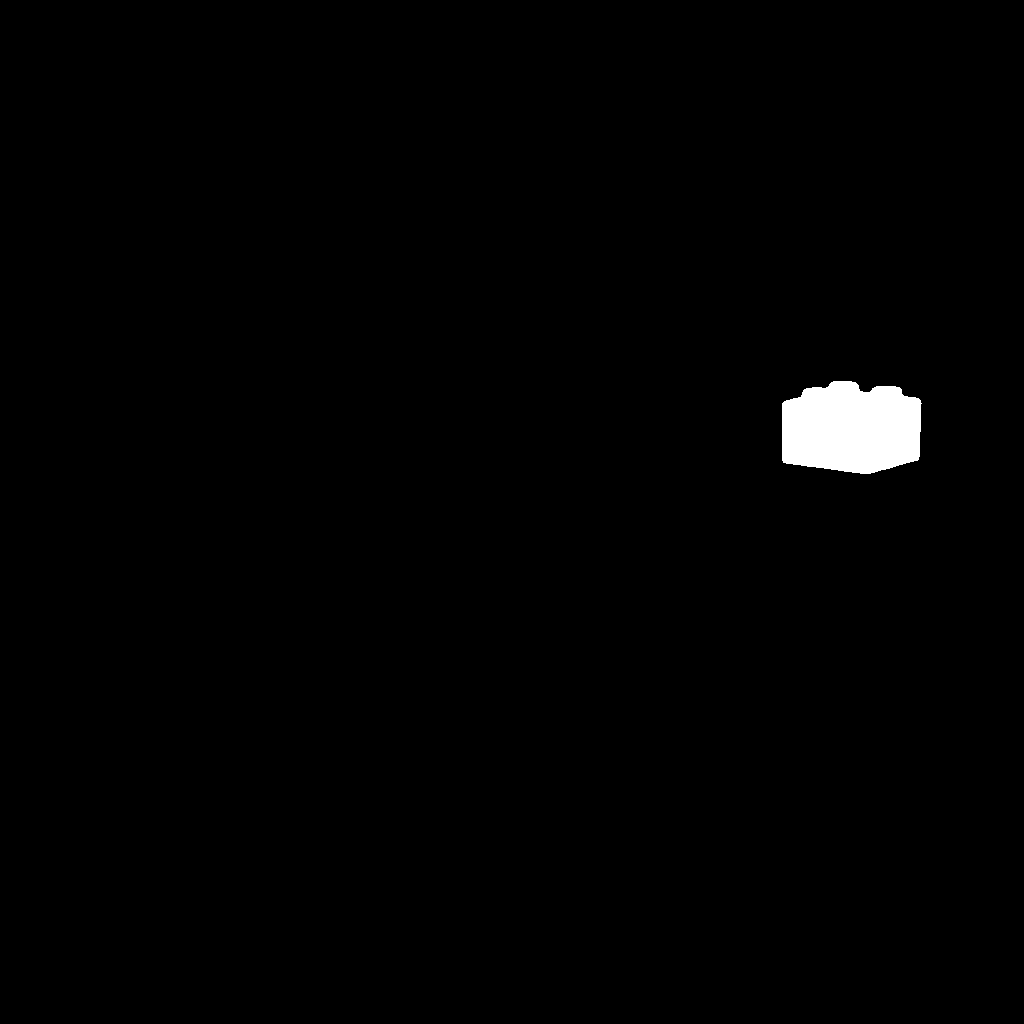

Now I have bounding boxes. But bounding boxes are rectangles, and objects aren’t. A bowl isn’t a rectangle. I need pixel-perfect masks.

SAM 3 (Segment Anything Model) is a promptable segmentation model—give it a hint about where an object is, and it figures out exactly which pixels belong to that object. The “hint” can be a point, a bounding box, or text. In my pipeline, I feed it the bounding boxes from GroundingDINO.

For each box, SAM returns a binary mask: these pixels are the object, these aren’t. The bowl’s curved rim, the block’s sharp edges—SAM captures it all with sub-pixel precision.

The tricky part was deduplication. A cup sitting on a saucer? Sometimes SAM would give me overlapping masks. I wrote code to check IoU (intersection over union) between masks and keep the better one. I also added an include_background flag for large objects like tables—more on that later.

|  |

|  |

| |

Each mask isolates a single object. SAM captures precise boundaries—curved rims, sharp edges, complex shapes.

Step 3: Turn 2D Masks into 3D Meshes

This is where the magic happens. I have a 2D image and a mask. I need a 3D mesh with textures.

SAM 3D Objects handles this. It’s a single-view 3D reconstruction model that takes a masked object and generates a textured mesh. Internally, it uses MoGe (Monocular Geometry) for depth estimation—figuring out how far away each pixel is from the camera.

The back of objects is always a guess since we only have one view. SAM 3D Objects hallucinates something plausible. A bowl’s back looks like… a bowl’s back. It won’t be photographically accurate, but for robot training, it’s good enough. The robot doesn’t care if the texture on the back is slightly wrong. It cares about the shape, the size, the physics.

The meshes come out normalized to about 1 meter. I scale them back to real-world dimensions using a category lookup:

| Category | Real-world Size |

|---|---|

| block | 5cm |

| bowl | 15cm |

| mug | 10cm |

| table | 80cm |

So when my pipeline sees “red plastic block,” it extracts the category “block” and scales the mesh to 5cm. “White ceramic bowl” becomes 15cm. This is where those descriptive labels from Step 1 pay off again—knowing “white ceramic bowl” instead of just “object_7” means I can scale it correctly.

Step 4: Make It Feel Real

A mesh isn’t enough for simulation. Isaac Sim needs physics properties. How heavy is this bowl? How slippery? Does it bounce?

This is where those descriptive labels from Step 1 pay off. Remember how Qwen didn’t just say “bowl”—it said “white ceramic bowl”? That “ceramic” part tells me everything I need about friction and bounciness.

For mass, I ask Qwen again, but this time with a physics question:

"This is a white ceramic bowl, approximately 15cm in diameter.

Estimate its mass in kilograms. Return only a number."

I ask three times with different temperature settings and take the highest answer. Why? LLMs tend to underestimate mass. They’ll say a ceramic bowl weighs 100 grams when the real answer is closer to 400 grams. Taking the max compensates for this bias.

For friction and restitution (bounciness), I extract the material from the label and use a lookup table:

| Material | Friction | Restitution |

|---|---|---|

| ceramic | 0.6 | 0.1 |

| plastic | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| wood | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| metal | 0.3 | 0.4 |

So “white ceramic bowl” gets friction 0.6 and restitution 0.1. “Red plastic block” gets friction 0.4 and restitution 0.3. It’s not perfect physics, but it’s close enough for training. The robot doesn’t need to know the exact coefficient of friction—it just needs objects that behave roughly like their real-world counterparts.

Step 5: Place Everything in 3D Space

Objects don’t float randomly. A mug sits on a table. A saucer goes under a cup.

Depth Anything V2 estimates how far each object is from the camera. Combined with the segmentation masks and some geometry, I can project everything into 3D space. Objects get placed at the right depth. Support relationships get detected—the system figures out that the mug is on the table, not hovering beside it.

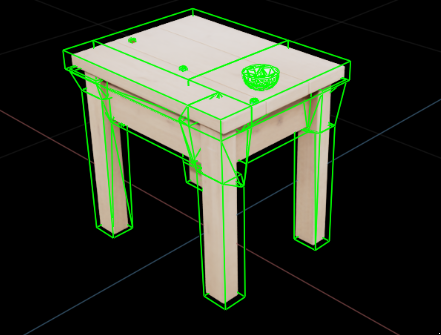

Everything exports to USD format for Isaac Sim. Ground planes get added. Collision meshes get generated using V-HACD (Volumetric Hierarchical Approximate Convex Decomposition), which breaks complex shapes into simple convex pieces that physics engines can handle efficiently.

The complete scene in Isaac Sim. Objects have correct positions, scales, and physics properties.

V-HACD breaks the bowl into convex pieces. Table legs get separate collision hulls for accurate physics.

Limitations

MARS is good at what it does, but it’s not magic. A few things it won’t handle:

Complex scenes with heavy occlusion. If objects are stacked, overlapping, or partially hidden, the pipeline struggles. The single-view reconstruction can’t see what’s behind the front object. Workaround: photograph individual objects separately and let the pipeline process them one at a time. More photos, better meshes.

Articulated objects. A laptop in your scene? MARS will reconstruct it as a solid block. It won’t know the lid opens. Same with books, drawers, scissors—anything with hinges or joints. The pipeline produces rigid meshes, not articulated models. If you need a robot to open a laptop, you’ll still need to model that joint by hand.

Deformable objects. Cloth, rope, soft toys—these get reconstructed as rigid shapes. A stuffed animal becomes a solid lump. Fine for collision, wrong for manipulation.

The sweet spot is solid, rigid objects: cups, blocks, bottles, bowls, tools. For everything else, the reconstructed objects can still serve as distractors in the scene—obstacles the robot needs to navigate around, just not interact with in complex ways.

What I Learned

Building MARS taught me that 80% of the work is plumbing. The AI models are incredible. Single-view 3D reconstruction basically works now. Vision-language models can estimate mass within 20% of reality. The hard part is making all these pieces talk to each other without crashing.

The pipeline now processes a typical scene in about two minutes on one GPU. Not real-time, but fast enough to generate hundreds of training environments overnight.

The Technical Bits

For those who want to dig deeper:

- Detection: Qwen 2.5-VL (7B) generates semantic labels (“white ceramic mug”). GroundingDINO uses those labels for precise bounding boxes. NMS removes duplicates. Neither model alone would work—Qwen can’t localize accurately, DINO can’t identify without prompts.

- Segmentation: SAM 3 with bbox prompts. Deduplication via IoU thresholding.

include_backgroundflag for large objects (tables, floors). - Reconstruction: SAM 3D Objects for single-view mesh generation. MoGe handles internal depth estimation. V-HACD generates convex decomposition collision meshes (also supports simple convex hull fallback).

- Physics: LLM-based mass estimation with temperature sampling (take max of 3 samples to counter underestimation bias). Category lookup table maps materials to friction/restitution values.

- Layout: Depth Anything V2 for scene depth. Support relationship detection for stacking. USD export for Isaac Sim.

- Validation: PyBullet physics simulation to verify stability before export. Objects that move more than 15cm during settling are flagged.

- Orchestration: Prefect for workflow management. Rich for terminal UI summaries.

The whole thing is modular. Swap out models, adjust thresholds, add new materials. It’s built for iteration.

If you’re drowning in manual asset creation for robot training, maybe a photo is all you need.

References

Inspiration

- RialTo: Reconciling Reality through Simulation - Real-to-sim-to-real approach for robust robotic manipulation

Vision & Detection

- Qwen 2.5-VL - Vision-language model for object identification and scene understanding

- GroundingDINO - Open-set object detection with language grounding

Segmentation

- SAM (Segment Anything) - Promptable image segmentation from Meta AI

3D Reconstruction

- SAM 3D Objects - Single-view 3D mesh generation from Stability AI

- MoGe - Monocular geometry estimation for depth prediction

Depth Estimation

- Depth Anything V2 - Robust monocular depth estimation

Physics & Simulation

- V-HACD - Volumetric hierarchical approximate convex decomposition

- PyBullet - Physics simulation for validation

- Isaac Sim - NVIDIA’s robotics simulation platform

Orchestration

- Prefect - Workflow orchestration for ML pipelines